Preface

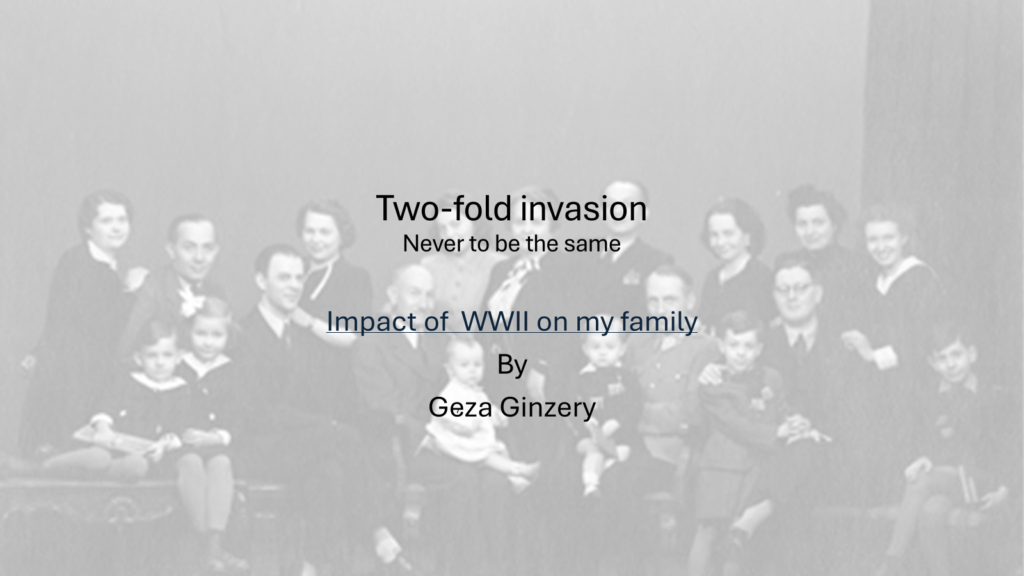

My name is Géza (Gaze uh). I was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1940, so I was only 4 or 5 years old for the war portion of this presentation.

A few weeks ago, my wife, Mary, and I were at the Galway library. There was a jigsaw puzzle on a card table, already started. I sat down and started to look for a piece that fit. Next thing I knew, our librarian, Deb, sat next to me and took my hand. I looked around to make sure that Mary was not around. I asked Deb what was up. She said, not letting go of my hand, that there was a plan to have a series of presentations about World War II and she wanted me to be one of the presenters, since I had personally experienced it. A flood of mixed feelings rushed into my head. I was flattered to be chosen, even though most of what I am going to talk about is already described in my website. To have my soul bared in front of strangers would be good for me and them, as well. I truly believe in the axiom “Who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” We have not heeded that warning and we are no closer to getting along with our fellow human beings. So, I told Deb that I would do it, so she let my hand go.

I am going to present my experiences in two parts: the good years for four years and the bad times lasting for 44 years, until 1989 when communism ended in Hungary. My bad days only lasted until 1956, when I left my homeland and ended up in this wonderful country, the circumstances of which I will talk about later.

A large portion of the credit for what you’re about to hear was due to my Mother’s uncanny ability to remember even the slightest details. She was a wonderful storyteller and was always the center of attention.

I brought two assistants with me tonight. First and foremost is my wife of 55 years, Mary. She is in charge of the artifacts.

My other assistant is Maria, who will be showing the computer-related pictures she ordered herself. I thank them both for their efforts.

It has been said that everybody’s life is a book. Well, peeps, get ready for a multi-volume book of adventure, comedy, with tearstains on many of its pages.

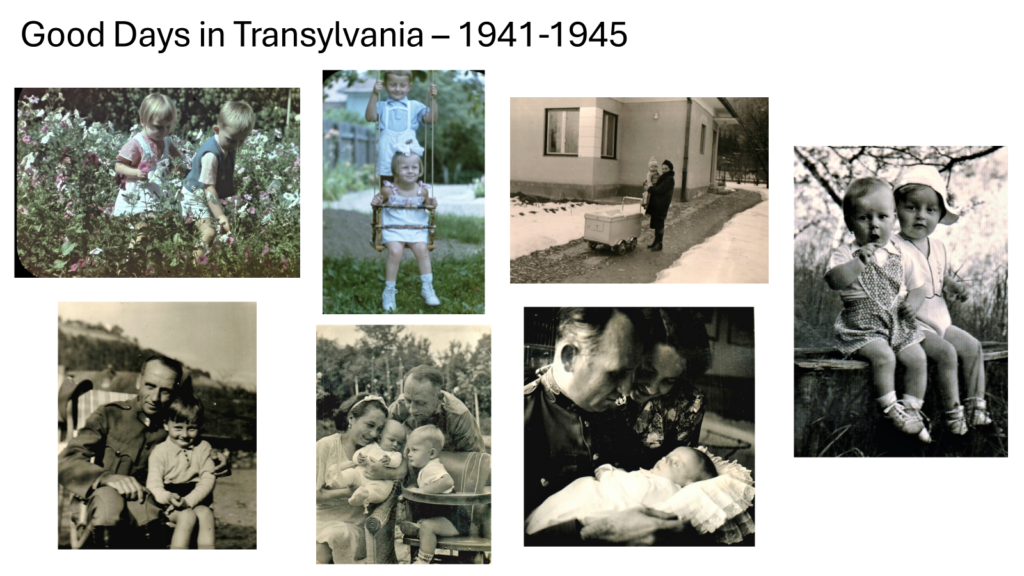

The good days in Transylvania 1941 through 1945

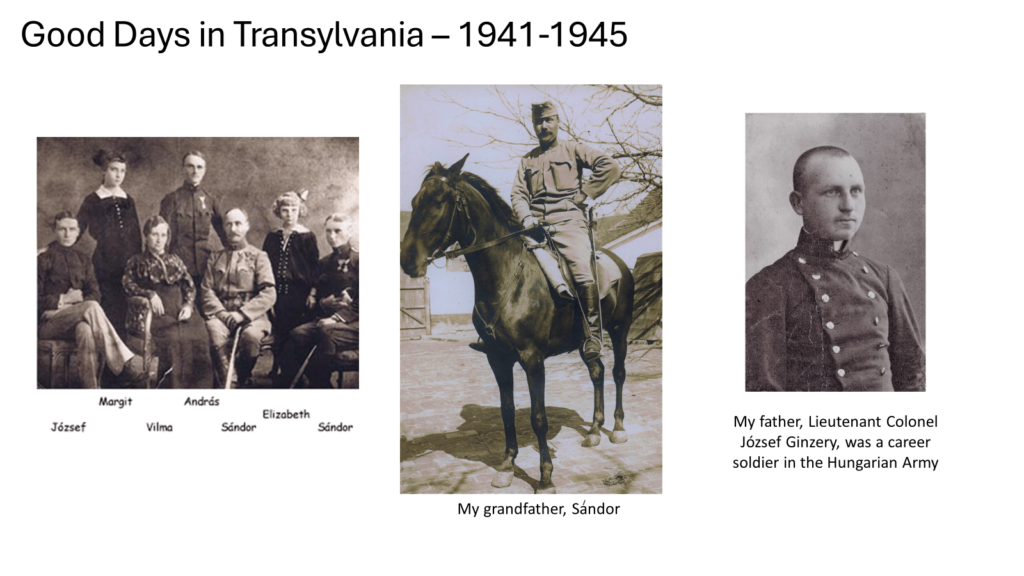

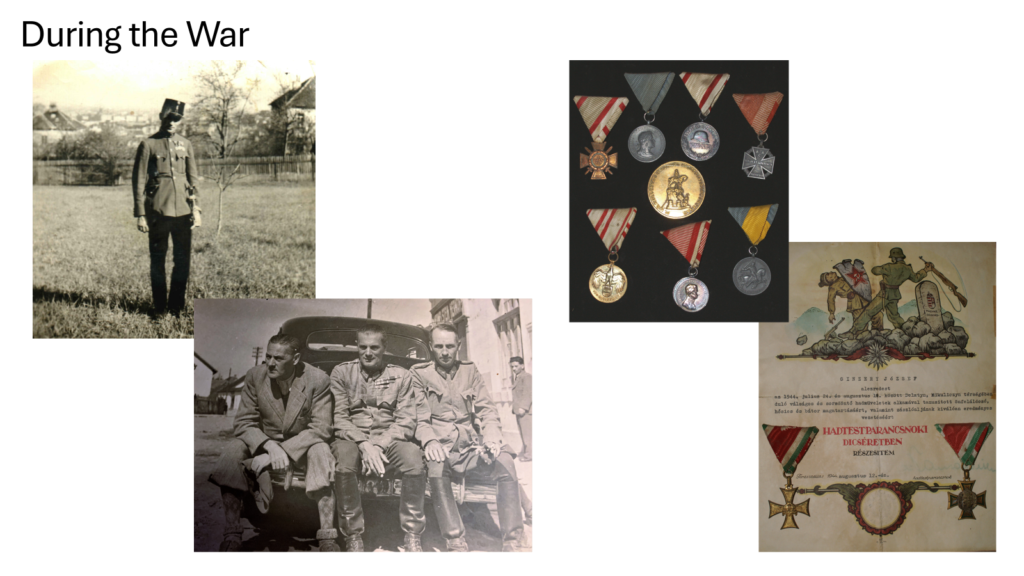

My father enlisted in the army before he was legally eligible. The fact that his father and two brothers were officers already had something to do with his decision. He fought in WW I.

In the early 1940s my family was living in Transylvania, where my Father was stationed. Many say that Transylvania was the most beautiful region of Hungary. It was doubly sad that it was lost after the first World War to Romania. He was a career officer holding the rank of lieutenant colonel, a level which afforded us a large house with sufficient land and soldiers to do the manual tasks, such as chopping wood, attending the flower and vegetable gardens.

As a career officer he was expected to maintain a certain level of existence. It meant that at the movies he was expected to buy tickets for the more expensive seats, which were at the back and when attending a play or an opera he was expected to occupy the more expensive front seats. He held season tickets for the operas. Gathering the stringent dowery caused a severe delay in my parents’ wedding plans, lasting for years before they had enough dowry.

They enjoyed a socially active life. There were many parties held at the house, with alcohol consumption and cigarettes. The attendees were all members of the military with my Mother in charge of the entertainment. The main attraction, however, was playing bridge. These parties occurred at regular intervals and lasted well into the night. Playing bridge was a life-long form of entertainment, bordering obsession. My first vocabulary contained bridge terms, I am sure.

Another hobby the family enjoyed was making oriental-quality rugs. They would hold races to see who would finish their rug first. A handful of examples of their work is in our house. Keep in mind that these were made before I was born, yet they are still in very good shape, despite my brother and his friend walking on them with ice skates strapped to their shoes.

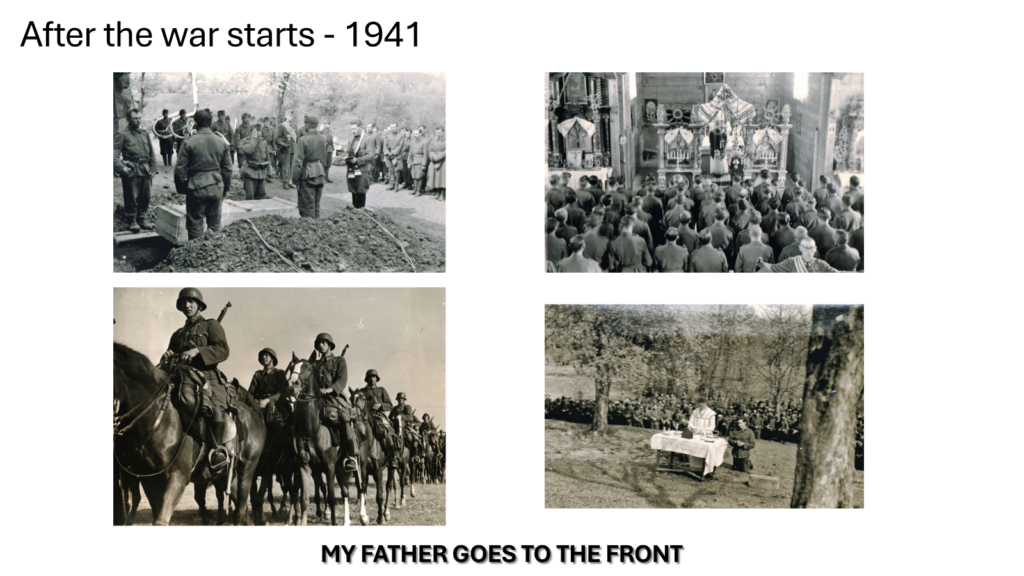

After the War Starts – 1941 (My father goes to the front)

After the war started and Hungary sided with Germany, my Father would go to the “front”. As a young guy, I couldn’t imagine what that must’ve been like. Not much about this was ever discussed, except according to my Mother, once he returned with 16 bullet holes in his car, another time his hair turned completely white. He never talked about his experiences at the front.

During the War

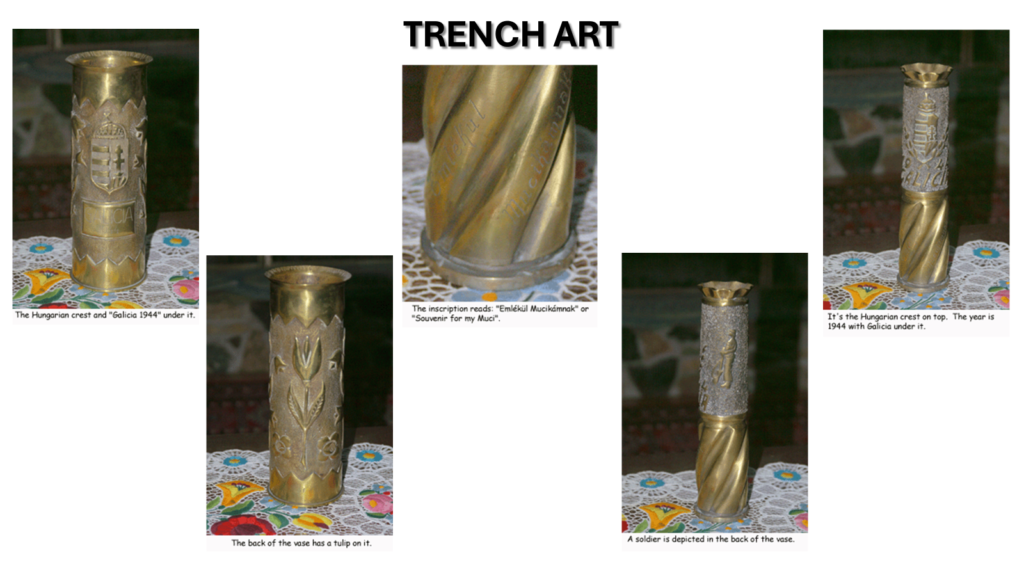

He was very much loved and respected by his soldiers. A group of them stayed up several nights to create a couple of fine examples of “trench art”, personalized for my Mother. Another soldier drew these three pictures and gave them to my Father. All of these have been cherished over the years and are now in my home.

I grew up here with my sister. She was a year younger than I but much more developed mentally. She developed a language that only the two of us could understand.

My Mother and sister were having a discussion about the birth of the baby my Mother was pregnant with. My sister said to our Mother: “If it’s a girl, we’ll name her Irén. If it’s a boy, you’ll name him Péter.” That is why my brother was named Peter.

The war reaches us – Russian Invasion 1944 – 1945

One of my first memories of the war is the first bombing I experienced at the age of 4. We were in a town when I heard the wailing of air raid sirens, soon to be followed by the sound of bombers flying overhead.

We quickly found a basement of a nearby building and waited for each bomb to explode. Each one was closer and closer. I was petrified, no matter how much my Mother tried to calm me. Even my sister stepped in, sounding like an adult. “Geza, it’s war.” I told you she was way ahead of me. The next thing I complained about “Why can’t I be served my food in my own dishes?” I was given leeway, because before I was born I had two baby brothers, both of whom died as infants.

My Father and his fellow officers realized that the war was lost, and we had to flee. We were given less than a week to pack our belongings into a box car. About half of the contents of the house was left behind due to lack of space.

We separated from my Father, who was to meet us later. Jumping ahead, we reached the Austrian border traveling in a bus full of families of other officers. My sister and I were sitting behind the driver on a mattress, with my Mother sitting behind us. There was a soldier sitting on the right fender of the bus, serving as a look-out. That soldier called back to the driver to stop, as there was a fighter plane heading for us. The driver stopped but an officer in the back of the bus yelled to keep going. The pilot went into a dive and started shooting at us. It was a British plane and to this day I have no desire to see any part of England.

It became noisy inside, with people screaming and bullets hitting metal and when I turned to my sister, I saw that most of her head was missing. Panicking people from the back of the bus were screaming as they stepped over injured people lying on the floor. It was then that I noticed that my mother was also injured. We found out later that a shrapnel entered her just below her left eye and exited halfway down her neck. She was bleeding profusely, and she thought she had lost an eye, as she couldn’t see. Somehow, in all the confusion, my Mother lost a little valet, which contained all our valuables. As If by a miracle, my Father found us and, after a short search, our valuables.

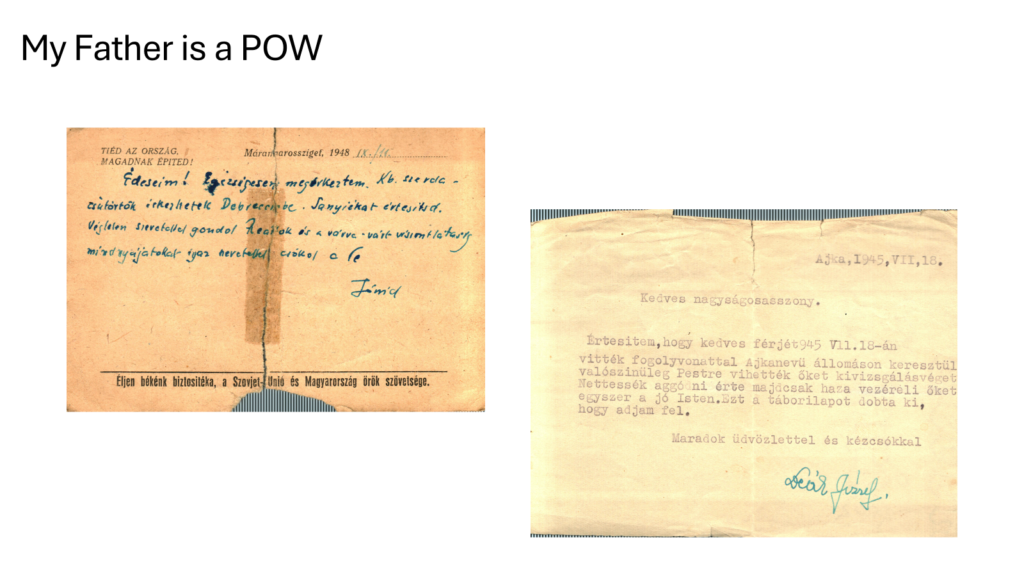

The next recollection is that my Father was captured and became a prisoner of war in Russia. After that he disappeared from our eyes for three and a half years.

My sister is buried in Austria. Don’t forget, my Mother was pregnant with my brother during all this.

My Father is a POW

Shortly after this, my Father was captured and the long trek to a Russian prisoner-of-war camp commenced. At first, they were on foot. It would have been easy to slip away into the night but the only thing the Russian guards cared about was the number of prisoners, so if they were short, they just captured somebody from the next village to make the numbers come out correctly. Freedom could also be bought for the price of a bottle of booze.

At some point the POWs were transferred to cattle cars with plenty of ventilation and zero heat. As they made their way to the prison camp, notes were written to loved ones back home and slipped through the cracks of the wagons. The locals would then pick them up and attempt to mail them. My father wrote several of these which found their way to my Mother. The notes only lasted for a week or so, after which no word was heard from my Father for three and a half years. I brought a couple of samples.

The note above says:

Dear Madame,

I am notifying you that they transported your dear husband through a station named Ajka on July 18, 1945. Please don’t worry about him. God will one of these days guide them home. I found your husband’s note asking me to send you this note.

I greet you with a hand-kiss

Deak Jozsef

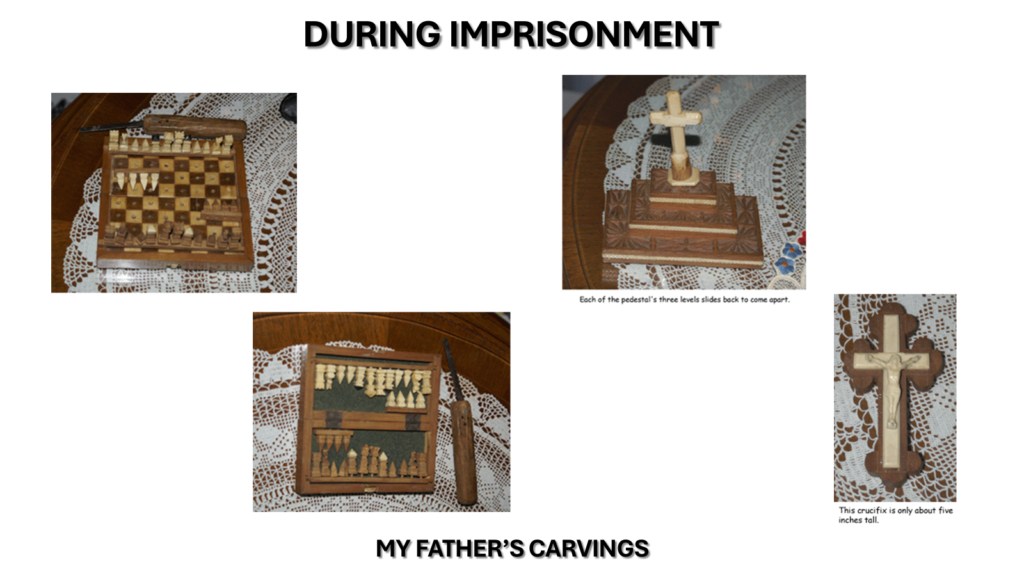

At the prison life was difficult, even though officers were not made to work. Not knowing one’s future gnaws at you every day. During his stay he made a friend, my namesake, Geza Nagy. Geza collected mushrooms and shared them with my Father, who credited him with saving his life. Food was pretty scarce. When one of the prisoners died, the others hid him from the guards for as long as they could, just to continue to receive the dead man’s ration.

My father took with him, from home, a silver spoon. He used it, while in prison, to get the last drop of food out of the dishes. It resulted in the end of it to wear down.

My father suffered from two rather serious conditions: stomach problems and a painful back problem. The constant diet of potatoes cured his stomach problem and sleeping on a thin layer of straw made his back problem go away.

I don’t know at which point in the three and a half years he started to carve items out of wood and bones he managed to take away from dogs. At the forefront of all the carved items is a folding travel chess set. It can be held closed by a clasp, which had been broken for years. On one of the many visits to Hungary he handed me the chess set to take with me. I asked him to fix the clasp before I took it home. He tried repeatedly without success, then handed it back to me saying he no longer had the patience to fix it.

Fertőszentmiklós is a little village in the northwestern corner of Hungary, It was to be our home for a few months. It was here that my brother, Peter, was born.

The village was occupied by Russians. Predictably their behavior was rude and crude. My Mother was five foot nothing, but she stood up to them denying their every offer. Once they came demanding chairs for a meeting they were to have. They promised to bring them back but my Mother still said no. She was winding her watch at the time and because she was nervous inside, she over-wound the watch. We still have it.

Finally, an officer came and requested the chairs in perfect Hungarian promising to bring them back. My Mother relented and we were happy to see her chairs being brought back after the meeting, while everybody else’s were left in a pile.

The people we stayed with treated us like family. We visited them once many years after the war and they greeted us with open arms.

It was a period of time when money was not worth much in a little village, Luckily, my Father had many nice clothes which my Mother traded for mostly food. You do whatever you can to survive.

Once, in an attempt to find relatives, we went to a much larger city, named Sopron. We did some hitchhiking and some walking. It was 19 miles away. I remember the bombed-out buildings, the smell of war, the people walking aimlessly, looking for something, but not knowing what. We never did find the relatives.

The next stop for us was Budapest, the small apartment of my maternal Grandparents and my Godparents. My Father was still in prison and my Mother’s shrapnel injury prevented her to work. Not to mention that she never held a job in her life. My Godparents, on the other hand, both worked.

Inflation hit Budapest hard, so much so, that when my Godmother got paid, in cash, she immediately went to the market to spend it because the next day it would be worth less.

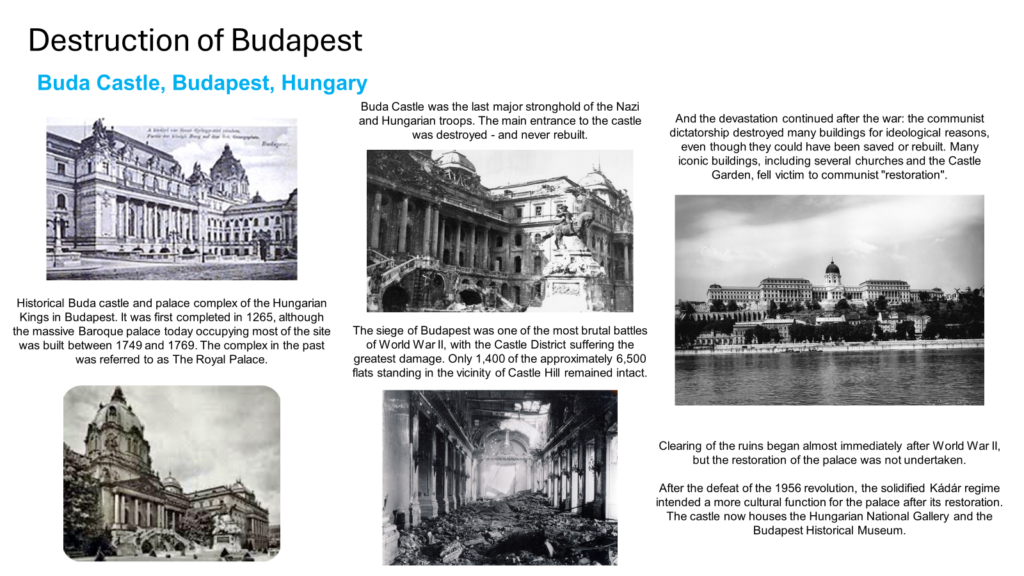

Destruction of Budapest

This was the King’s Palace. It had 365 rooms. After the restoration it became a museum.

This is my favorite church.

This is Mary’s favorite bridge. Every time we went to Hungary, we visited this bridge. It is called the Chain Bridge because is was made from links. On each side at the beginning of the bridge is a lion statue. A boy once noted that the builder forgot the lion’s tongue, as the lion’s had no tongues..

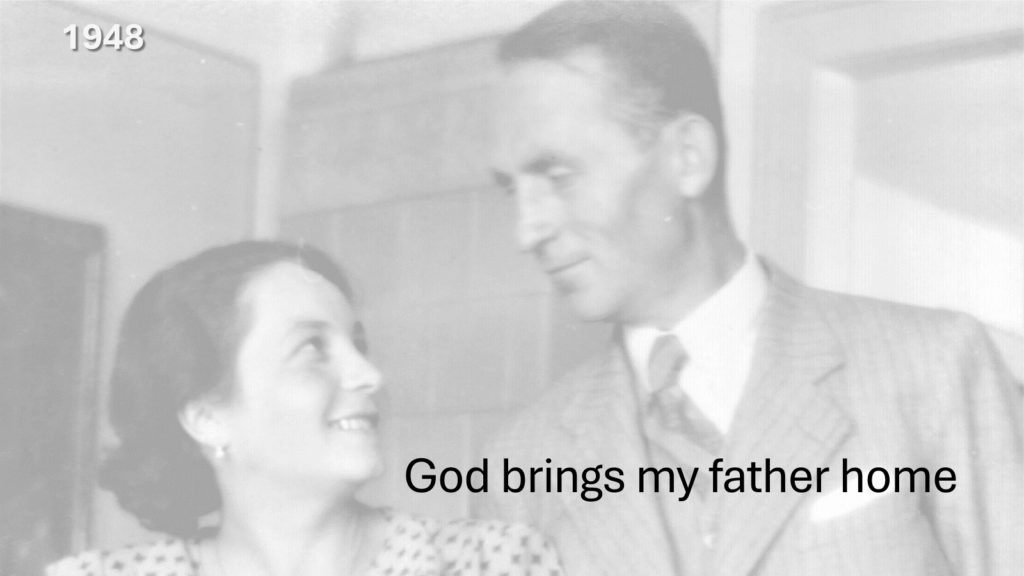

God brings my Father home

In 1948, after a three-and-a-half-year absence, my Father returned home. He lost almost half his body weight, and he stank, so he was hardly recognizable. While he was in prison my Mother kept showing my brother my Father’s picture. That picture was much different than the man who was now part of our family, that Peter feared his own father for weeks.

My Father’s next hurdle was to find a job. By this time communism had taken over Hungary to become one of the so-called Iron Curtain countries. Because he fought on the wrong side, he was blacklisted and after much time searching for employment, he had to settle for a job in a factory at the age of 51. He was 76 when he retired from this job. Because of him, I and Peter too was on the blacklist and college education would have been denied to us. That is why my parents decided to send me to this wonderful country. But that’s another cup of coffee.

Life under communism

Things I remember:

- Two government representatives rang the doorbell one day and announced that they were here to inspect the apartment to see if it was too big for the number of occupants. The inspection revealed that indeed it was, so they would be back with the people to move in. My Mother found a couple, through my Aunt, and by the next day they moved in. They ended up living with us for many a decade.

- The new couple were pharmacists and most of the time they ate out, had no children and were unobtrusive. They had no radio and when they bought one, it only had the two stations controlled by the government.

- My parents grilled me regularly to watch what I say because teachers were known to question children about the parents’ conversation at home. If it was anti-government they would turn the parents in for favors.

- Conversations in public only took place after making sure nobody was listening.

- The government desperately needed foreign currency. To that end there was a store close to where many tourists gathered. Unlike any other store in the city, it was loaded with merchandise which could only be purchased with foreign money. Keep in mind that the citizenry was not allowed to have foreign currency. It was pitiful to watch some people pressing their faces against the window.

- For a while after the revolution Hungarians were not allowed to leave the country. Later, if a Hungarian citizen wanted to have a vacation outside Hungary, he was allowed to leave but could only take five dollars with him. The first time I went back to Hungary an acquaintance gave me a twenty-dollar Australian money and asked me to mail it to somebody in West Germany. Once he got enough money that way, then he could go on vacation. I mailed a twenty American dollar instead and started to collect money after that.

- Standing in line for everything, this was my job and hence I hate lines to this day.

- Saving everything, plastic bags, strings, etc.

- On public transportation, everyone wore drab clothing and stared at their feet. When a tourist got on, everyone stared at them. During this time, my Mother always dressed up and wore gloves. Hence everyone stared at her.

- Many of the buildings damaged by the war were never fully restored as a reminder. But the buildings in the areas frequented by tourists were restored.

- Árpi was my best friend in high school in Budapest. We were very close and kept in touch even after I left the country for Austria. My letters to him were opened by the government and on several occasions, he was brought in for questioning by the Russians. Fortunately, he was always let go. A particular house, where they did this questioning, had a reputation for punishing “Crimes” against the government. Reportedly, there was a tunnel leading from this building to the Danube and many people were never seen again. My father was also summoned several times for questioning but was also fortunate to be let go.

The Revolution

Then in 1956 the unthinkable happened. A large group of college students staged a demonstration in front of the radio station. It spread like wildfire and before long much of the downtown area of the city joined them. The radio station was taken over and victory was declared. It was very short-lived, as a few days later the Russian militia moved in and surrounded the city, and the shelling commenced. Artillery shells were flying, exploding at different distances. It was a scary experience. One of these shells ended up on the fifth floor of our apartment building, in one of our neighbor’s clothes closet, unexploded. It was an incendiary bomb, so we were very lucky it didn’t explode. Small arms fire was heard almost all the time, mostly originating from the nearby park, where a lot of the fighting took place. All the stores were closed, and nobody went to work or to school. I remember waking up that morning to hear the pendulum of the wall clock above my head hitting the side of the clock. At first, I thought it was an earthquake. We tried listening to Radio Free Europe to find out what happened. Of course, it was jammed, and we only understood bits and pieces.

Finally, through word of mouth we learned what happened. On October 23rd, 1956, there was a revolution, an uprising of the people, who’ve had enough of communism. Many gave their lives, most of them young people. One of my classmates, an excellent gymnast, lost his life during this time. It wasn’t long before the Russians quelled the fighting. It was all but over in early November and there was an eerie quietness in the city. We went for a walk. The buildings wore the results of the heavy shelling. At most intersections a Russian tank was placed strategically pointing down the street with its cannon. It was eerie to walk towards one of these, as you were never sure that it was unmanned. There were dead bodies everywhere, most of them covered with lime powder. I saw several Russian soldiers lying on the ground, victims of the famed Molotov cocktails used on their tanks. A glass bottle filled with gasoline with a rag sticking out of it for a fuse. Lighting the rag and throwing the bottle at the tank made a very efficient weapon. This was named after the Russian General that led the Russian militia. The dead Russian bodies shrank from the heat to resemble those of children. It was really grotesque.

Making plans for a new life

My Father’s best friend and his wife became frequent visitors to the apartment. As always, we, the children, were in another room, but we did hear quiet discussions from the adults. They finally revealed that they had been making plans for my future and the future of the children of his best friend.

Before I can proceed, I need to say a few words about the “Iron Curtain”. This was an entity which was part physical and part mystical. For a hundred or so feet from the border on the inside of the country all trees and bushes were destroyed. Land mines were buried in this swatch of land to indiscriminately kill all life that happened to step on them. To fortify the border even more, tall machine gun towers were erected within sight of each other, equipped with powerful search lights and machine guns.

Additionally, it was forbidden to travel within a few miles of the border. In those days permits were required to travel anywhere and if you were caught in this forbidden zone without a permit, your fate might never be learned by your loved ones.

Back to the story. There was a period of a few days when the so-called Iron Curtain did not exist. The machine gun towers were left unmanned in sympathy for the freedom fighters, some of the mines were disposed of by the locals, who knew the area. It was this window of opportunity my parents chose for me. At this time my brother, Peter, was 11 years old, too young to come with me. My mother didn’t want to leave her father behind. My father felt that he was too old to start a new life in the US at the age of 58 and he didn’t want to be a burden to his sisters.

I don’t remember what I took with me on this trip. The truck pulled up to our guide’s home, very close to the border. This would be our home for the night. I remember it was a peasant house and I couldn’t sleep for the excitement and the excessive amount of heat generated by the feather bed. It was the middle of the night when we were awakened, and it was time to walk across the border. We were asked to be quiet and careful walking in the darkness. We came upon a small building close enough that we could see the soldiers inside and heard them talk and laugh raucously. As we kept walking, keeping one eye on the windows of the building, all went quiet, and the inside lights were doused, and bright outside lights were turned on. Everybody dropped to the ground, and it seemed an eternity before the outside lights were turned off and all returned to normal, including our heartbeats.

We walked for a long time before we came to some railroad tracks. Our guide said that if we followed the tracks in the direction he pointed, we would be in Austria before too long. He bid us good luck and disappeared. We reluctantly started to walk but stories of other guides, where they guided refugees back to the Russians. were in the back of our minds. When we arrived at the little train station and saw the German writing on the wall, we knew we were safe. The name on the wall was Pamhagen, and that is how we knew we were in Austria.

Time in Austria

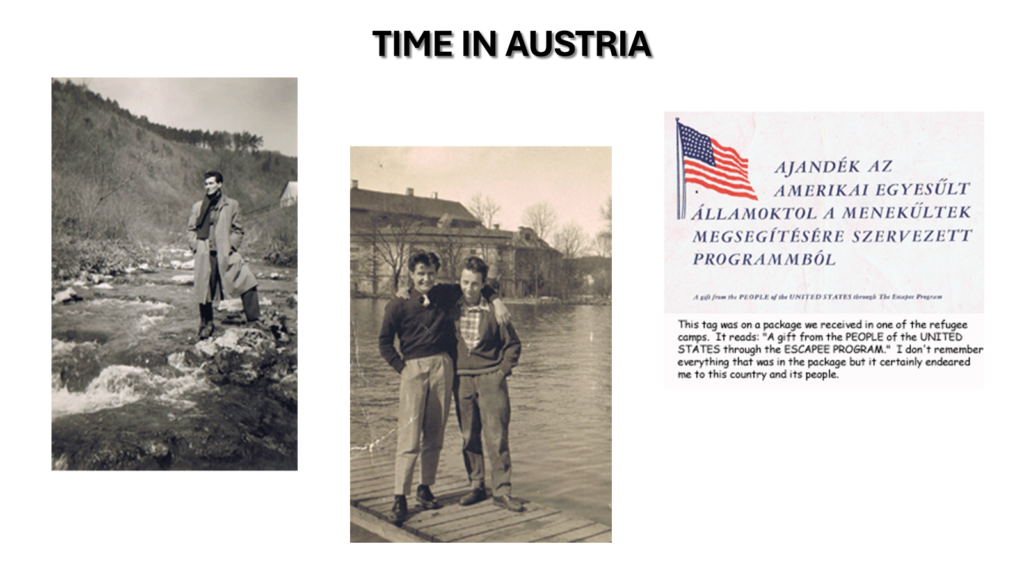

Prior to the revolution there was a quota system in place for each country for letting immigrants into the US. After the revolution the number of refugees and the quota system created a long waiting list. Only blood relatives were allowed to enter. Luckily, I qualified, and my uncle and two aunts were totally responsible for me.

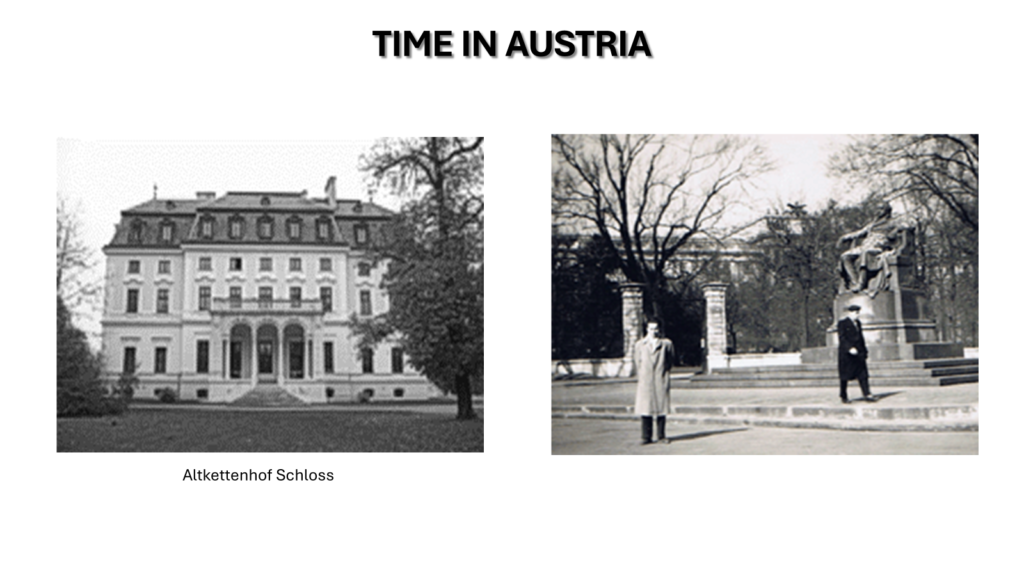

I spent the next 15 months in different refugee camps in two different regions of Austria. At first, we stayed around the beautiful city of Vienna. One of the camps (lager is German) we stayed in was a private palace at one time called Altkettenhof Schloss. It was still beautiful and very spacious. I played ping pong incessantly and became pretty good at it.

I spent a year in Vienna in different places in the city. We walked all over, as we didn’t have much money. We got our hair cut in a barber school for free. We stayed in empty school buildings, where they had restaurant-sized containers of yellow cheese sitting in the windowsills. That was what we had for snacks. To this day, I turn up my nose at yellow cheese.

Time in Kammer/Attersee

After that, another year was spent in the foothills of the Austrian Alps in a Hungarian Middle School, Kammer/Attersee for Hungarian refugees. This is where I started smoking.

There were many of us boys living in this building. It was run by catholic priests, who held a very tight rein on us. There was a schedule that had to be followed and regular classes to be attended daily. There was German and Latin to be learned. We did have some free time, some of which I used to read stories in English-language Reader’s Digests I bought in Vienna. When I came to a word I didn’t know, I would write the English word on a piece of paper, look up the Hungarian word for it in my dictionary and write it next to the English word. The piece of paper remained with the story in the magazine.

One day an American movie was playing in the only movie house in Kammer am Attersee. Many of us wanted to see it, so a delegation was formed and formal permission was asked for from the principal of the school. It was denied. We were very upset and a few of us decided that we were going to see the movie, no matter what. The name of the movie was The Glen Miller Story and I kept the ticket as a souvenir. I still have it. After lights-out we tied a bunch of sheets together and lowered ourselves down to the ground. One rather chubby boy stayed behind and was supposed to lower the sheets when we got home. We fixed the beds as best as we could to resemble someone sleeping there. Once on the ground we went to the movies. We went inside and immediately realized we were in trouble because a lot of our teachers were also there. I thoroughly enjoyed the music in the movie, even though I couldn’t understand the words and it is still one of my favorites.

After the movie we assembled outside the movie house within sight of the teachers. We marched in formation (like we did every Sunday to and from the church), someone was shouting one… two… one… two in the front and marched toward the school. When we neared the familiar building all the lights were on.

The principal, a very large man, was blocking the doorway, preventing our entry. He made it clear to us that we were not coming in. A little discouraged but too proud to admit it, we got into formation again and kept on marching. We found a field with haystacks and slept in the hay like babies. The next morning, we went back to the school, and all was forgiven.

At one point, I had heard that the Hungarian government punished all those who left the country during the revolution by forbidding them to ever enter the borders again. My Hungarian citizenship stripped from me; I was now really homeless.

Let me pause again, to say some words about the Austrians. They had also suffered much during the war and were still rebuilding. I was very grateful for how they opened their arms to accepting us refugees so warmly.

During my time in Austria, several “salesmen” showed up offering opportunities to work in coal mines in England. Another person gave a very persuasive talk about life in America, should you accept his offer to go there. According to him, you would receive a car as soon as you landed. If anything should happen to that car, you would walk to the nearest tree, where there was a phone. You would make a call and a new car would be delivered to you. I believed this story, since we were told many times that the roads of America were paved in gold. Fortunately, I didn’t accept any of these opportunities, since I already had a path to the US planned.

My Path to the US

I was finally notified that I am to start my journey to the US. I took off from the Schwechat airport in a propeller-driven airplane, heading for New York. Traveling through the night we finally arrived, around 7am, in Idlewild airport, which is now JFK. It was under construction. To this day, I have never seen an airport that was not under construction.

I was met by the representative from the catholic organizations who sponsored my journey. A cab ride later we arrived where all the skyscrapers lived, I couldn’t believe what I saw. My neck was killing me. I felt like a dog with his head out the window. Frankly, I don’t know how dogs do it.

We arrived in short order in front of Grand Central Station, a marvelous building. I only had one piece of luggage, but it was HUGE and half of it was filled with the Reader’s Digests from Austria. After a while I could only drag it on the floor for the weight. I was mesmerized by a huge American car spinning on a turnstile in the huge foyer of the station. I was trying to keep up with my escort but couldn’t take my eyes off the car. I had never seen a car that big. Remember, this was 1958 and the cars had huge fins on the back.

We ended up below the ground and boarded a train. My escort sat me on a seat, said his goodbyes and disappeared. I was trying to catch my breath as I looked around me. The car started to fill up and before too long we pulled out of the station. Nobody gave me a second look despite my appearance. My aunts had sent me a camel hair winter coat in a package while I was in Austria. I thought it was too long for me, so I altered it myself. I cut several inches off the bottom and then I sewed in a hemline by hand. Unfortunately, I only had black thread. Pinned on the lapel of that coat was a tag, announcing to the world that I was a Hungarian Refugee. At a time when 99% of the boys of my age wore crew cuts, I had a huge head of hair, bigger than Elvis’.

The hours wiled away as the scenery out the window no longer included tall buildings but open fields. We stopped quite often; more people would get off, few would board, until the only people in the car were a group of five men playing cards in the back and I, in the front. Somewhere along the way I had lost my lighter and it’s been hours since I had a cigarette. I had no idea how long the train ride was or even when and where I was supposed to get off. All that together gave me the courage to ask for a light for my cigarette. I held a cigarette between my fingers, and walking toward the card-playing men, I held up my hand and said: “Fire.”. This is how you ask for a light in German and in Hungarian. They turned and looked at me strangely for a second but then put two and two together and one of them tossed me a book of matches. I took one to light my cigarette, then handed the rest back to its owner. He made me understand that I could keep them. Wow! This guy must be a millionaire to be giving matches away like that. You see, in the parts of Europe where I had just come from, you had to buy the matches with the cigarettes. Finally, I couldn’t stand it anymore and, in my head, I formulated a sentence, using all my English grammar and vocabulary, to ask the conductor when I was supposed to get off. He showed me that when he took the little stub away from the top of the back of the seat in front of me, the next stop is mine. Now I could relax a little.

It was dark by the time we arrived in Ithaca. I had no idea what my relatives looked like, luckily there were only a few of us getting off the train and even less people waiting to meet us. My two aunts and uncle and my younger cousin, George, met us at the station. He was (and still is) a year younger than I. We conversed in Hungarian, of course, all the way home. George spoke Hungarian, although with an accent and my aunts and uncle spoke perfect Hungarian, naturally, but with a few English words indiscriminately thrown in. Three weeks after I arrived in the US, I attended senior year with my cousin and also already had a job. I was 18 years old.

The left map shows where Hungary is geographically located, with Transylvania in the lower right orange area. The one on the right is a map of Hungary before WWI and after WWII. The dark area is the land taken away from Hungary during the wars, with the light grey area being what remains.

In Conclusion

Directly due to the war nine family members left Hungary and contact with them was never the same. Leaving Hungary was beneficial for me, and I consider it the biggest break of my fife but those who got left behind suffered beyond description.

All of these experiences made my parents and me stronger.

The major takeaway from this project is that if you’re thinking of writing such a book, do it now while all the characters are still alive. Once they’re gone, there is no one left to answer your queries.

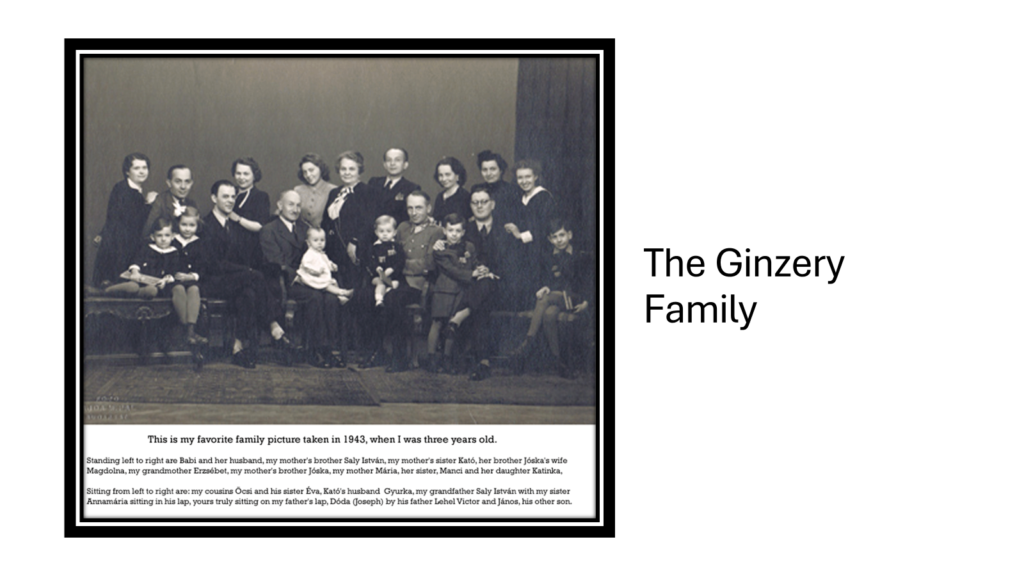

This is my favorite picture of my family.

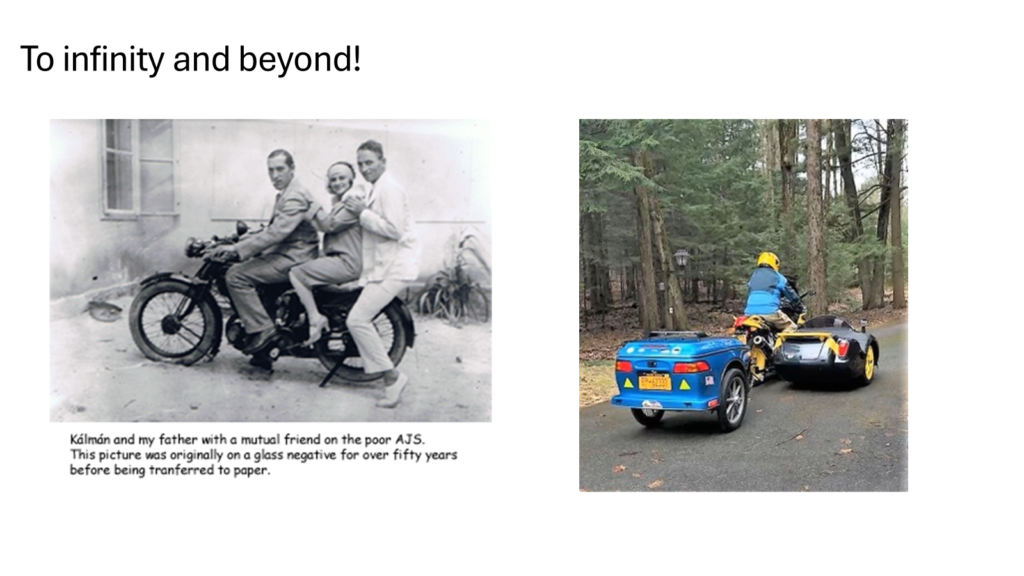

My Father was a motorcyclist and so am I.

Recommended Viewing

http://maryandgeza.com website contains much more of my life experiences, trips taken to Europe and the US.

Moscow on the Hudson with Robin Williams shows how you always stood inline, even if you didn’t know what was selling at the front of the line.

The Pianist with Adrian Brody – available free on the Internet. It shows you how wars strip people’s dignity and self-worth.